Giochi dell'Oca e di percorso

(by Luigi Ciompi & Adrian Seville)

(by Luigi Ciompi & Adrian Seville)

|

Giochi dell'Oca e di percorso

(by Luigi Ciompi & Adrian Seville) |

|

|

Torna alla ricerca giochi (back to game search) |

|

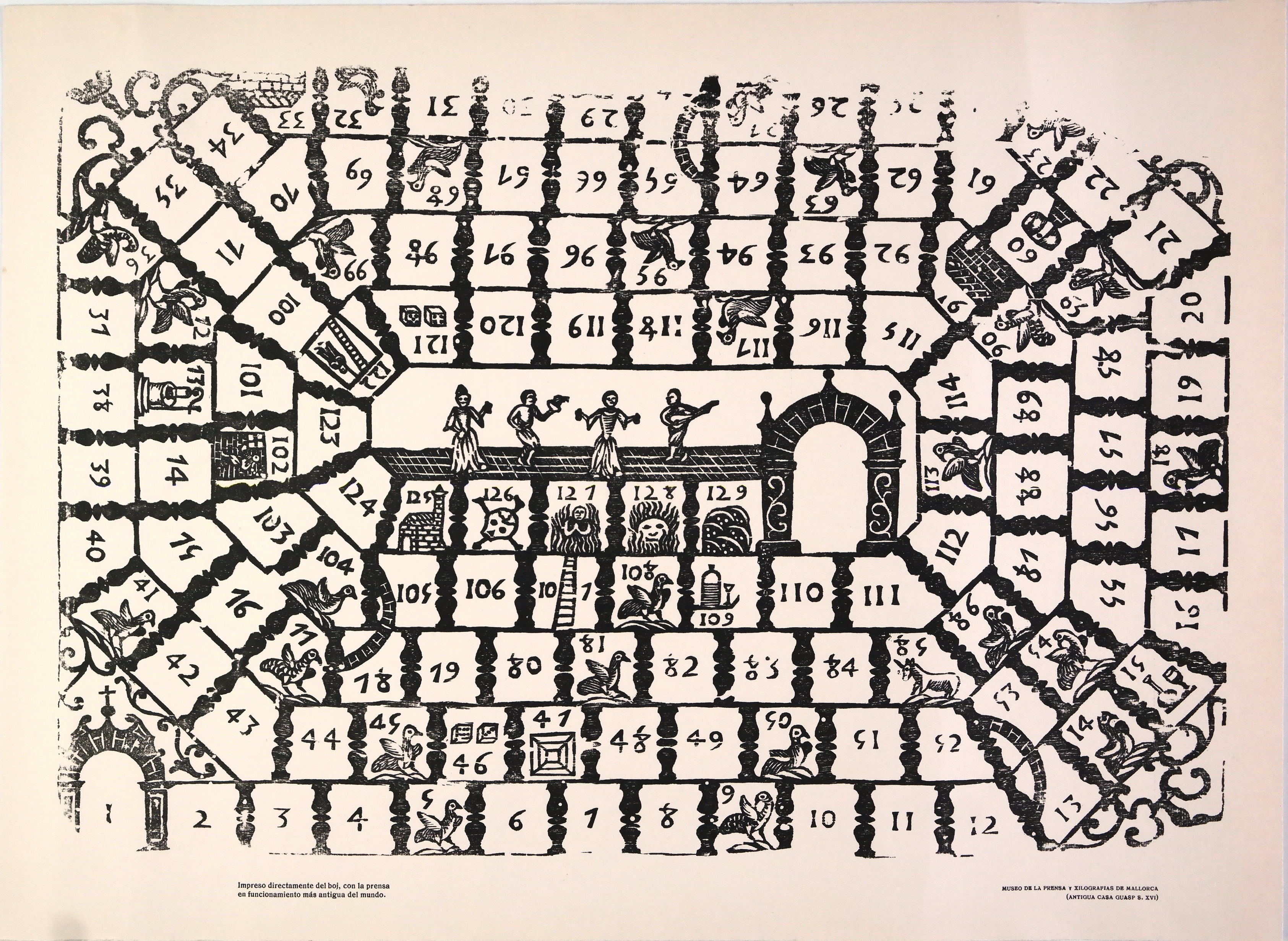

| Senza titolo - Untitled (Joc de l'Oca) (fac-simile) | ||

|

Versione stampabile

|

Invia una segnalazione

|

|

primo autore: | Anonimo |

| secondo autore: | Antigua Casa Felip Guasp | |

| anno: | 1650/1700 | |

| luogo: |

Spagna-Mallorca |

|

| periodo: | XVII secolo ?/4 | |

| percorso: | Percorso di 129 caselle numerate | |

| materiale: | carta (paper) (papier) | |

| dimensioni: | 000X000 | |

| stampa: | Stampa su legno (bois gravé) (woodcut) | |

| luogo acquisto: | ||

| data acquisto: | ||

| dimensioni confezione: | ||

| numero caselle: | 129 | |

| categoria: | Oca | |

| tipo di gioco: | Gioco con oca | |

| editore: | Antigua Casa Guasp | |

| stampatore: | Antigua Casa Guasp | |

| proprietario: | Collezione A. Seville | |

| autore delle foto: | A. Seville | |

| numero di catalogo: | 2582 | |

| descrizione: |

Gioco di 129 caselle numerate, spirale (rettangolare), antiorario, centripeto. REGOLE: non riportate sul tavoliere. CASELLE: mute. REFERENZA 1 The Game of the Goose (Juego de la Oca) came to Spain towards the end of the 16th century, as a royal gift to Philip II, giving rise to the variant game of the Filosofia Cortesana invented by Alonso de Barros. It is not known whether the game that came to the Spanish Court was of the classic form, though the fact that the de Barros game is of 63 spaces arranged as an anticlockwise spiral in vertical format strongly suggests that it was, although the placement of hazards does not conform to the classic model. Also, only some but not all of the earliest surviving Spanish games dating from the 17th century that show the image of the goose on the favourable spaces are of the classic form. However, the classic game survives to the present day as a game for children that can be bought in Spanish toyshops, often printed in bold colours on a wooden board of square format, frequently having a version of Ludo for six players printed on the other side. The "reverse overthrow" rule is usually replaced by the rule that, beyond space 60, a single die is used. This greatly diminishes the excitement of the game since there is no possibility of reaching the death space and being required to start again. Spain does not seem to have shared in the transformation to thematic variants that occurred so remarkably in France from the middle of the 17th century, nor in the introduction of "monkey" games and "journey" games that became so popular in Germany from the end of the 18th century onwards. In Portugal a distinctive form of the game is the "Joco de Gloria", which employs an anticlockwise spiral track of 90 spaces, with the favourable spaces on 9, 18, 27 etc. The track length suggests that this is based on the Italian variants from the second half of the 19th century and indeed the earliest examples appear to date from that period. The Portuguese firm Majora, established in 1939, continues to supply modern versions of these games. Both Spain and Portugal are significant in the spread of games of the Goose type to the countries of Latin America, where they continue to be played. The earliest Spanish Games of the Goose Amades gives as the earliest Spanish Game of the Goose known to him a 17th-century Catalan example in the Municipal Museum of Barcelona (Arch. n°1440). It is a rather crude wood-cut, with a rectangular spiral track of 141 numbered spaces plus the final un-numbered arch of the winning space. The geese are on two sequences of spaces numbered 5, 14, 23 etc to 131 and 9, 18, 27 etc to 126. No rules are given, so that it is not possible to interpret the hazard spaces definitively, though some of the traditional hazards are recognisable: the well, at 82; stylised labyrinth at 98; and a death's head at 138. There are however further hazards, such as a barrel at 51, a decanter and glass at 64 and a wine jar and glass at 127, suggesting that this was a drinking game. Dice spaces appear at 52 (for the 6, 3 throw of nine) and at 133 (for the 5, 4 throw). The final five spaces before the winning arch all have images and appear below a stylised garden with four trees. Amades notes that the ladder at space 119 leads to a space (140) that he interprets as Hell next to Purgatory (space 141 showing rudimentary human faces) which in turn is next to the sky (presumably the blank arch) which leads to the garden. He notes the figure hanging from a gibbet at space 135 and connects this with the path to Hell. A more plausible interpretation is to consider the final spaces as providing a connected narrative: prison (space 137), death, burning of a heretic, Hell, Purgatory, then Heaven as symbolised by the Paradise Garden. A fascinating comparison is possible with another 17th-century game also noted by Amades, of which he remarks that the central space is decorated with dancing figures that have nothing to do with the game: he speculates that the reward of the winner might be to dance with the girls or ladies of the party, though he gives no evidence for this. The final spaces correspond to those of the earlier game, except that spaces 127 and 128 reverse the order of the images. By contrast, a second 17th-century woodblock conserved at the Impresa Guasp (Arch. n°2662) is in fact a classic Game of the Goose in all respects save one: the prison space at 52 shows a barrel, indicating that this too was a drinking game. The centre space shows coins, indicating gambling, and also a walled garden. This is a clear representation of the Garden of Eden, as indicated by the four-fold division symbolising the mystic four rivers; the Tree of Life occupies one quarter. Amades shows another 63-spaces Game of the Goose, this being a Catalan woodcut by Michael Homs of Gerona dating from the end of the 17th century; the block is conserved at the Imprenta Carreres. This is an absolutely classic game as far the arrangement and iconography of the active spaces are concerned; the rules are given in letterpress in the centre, under the heading "Declaration" and include the rule that from space 60 a single die is to be used. The incidental iconography is interesting: the winning space shows a portal internally studded with threatening spikes. The corner decorations include one showing a hooded figure with a sword in one hand fending off a large dog using a staff held in the other. Stylised birds, a dog evidently crawling through a barrel, and a drummer complete the remaining corners. This decorative scheme is essentially the same as that found in an 18th-century French woodcut "jeu de l'oie", by Leblond, rue de la Bonneterie, Avignon, though in this version the second dog appears to be wearing a cloth round his middle. The iconography of the active spaces does not correspond exactly with that of the Spanish version: for example, the bridge at spaces 6 has three piers instead of two, so these are not exact copies. The French print also gives rules, which include the usual reverse overthrow provision. (Adrian Seville) Exhibitions: |

|

| bibliografia: |

1) BLAU, J.L. : "The Christian Interpretation of the Cabala in the Renaissance, Columbia University Press,1944. 2) BROWNE, Sir Thomas: "Pseudodoxia Epidemica, ChXII", 1650. 3) BUIJNSTERS, P.J. and Buijnsters-Smets,L. : "Papertoys", Zwolle, Waanders, 2005. 4) CARRERA, P. : "Il Gioco degli Scacchi", Militello, page 25, 1617. 5) CULIN, S. : "Chess and Playing Cards", University of Pennsylvania, pages 843-848, 1895. 6) D’ALLEMAGNE,H. R. : "Le Noble Jeu de l’Oie", Paris, Libraire Gruend, 1950. 7) DOMINI, D. : (in) "La Vite e il Vino" (exhibition catalogue), Fondazione Lungarotti, pages 37-38, 1999. 8) GIRARD A. R. and QUETEL, C. : "L'histoire de France racontée par le jeu de l'oie", Paris, Balland/Massin, 1982. 9) HANNAS, L. : "The English Jigsaw Puzzle", London, Wayland, page 115, 1972. 10) HIMMELHEBER, G. : "Spiele – Gesellschaftspiele aus einem Jahrtausend",Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1972. 11) HUFMANN C.C. :"Elizabethan Impressions: John Wolfe and His Press, New York, AMS Press; 1988. 12) MASCHERONI S. and TINTI, B. : "Il Gioco dell'Oca", Milano, Bompiani, 1981. 13) MENESTRIER, C. F. : "Bibliotheque Curieuse et Instructive", Trevoux, page 196, 1704. 14) MURRAY H. J. R. : "A History of Board Games Other Than Chess", Oxford University Press, pp 142-143, 1952. 15) SEVILLE, Adrian:"Tradition and Variation in the Game of Goose", in: "Board Games in Academia III", Firenze, Aprile 1999. (aggiornamento del 2005). 16) SEVILLE, Adrian: "The sociable Game of the Goose", in "Board Games Studies Colloquia XI", 23-26 Aprile 2008, Lisbona - Portogallo. 2008. 17) SEVILLE, Adrian: "The Royal Game of the Goose four hundred years of printed Board Games". Catalogue of an Exhibition at the Grolier Club, February 23 - May 14, 2016. 18) VON WILCKENS, L. : "Spiel, Spiele, Kinderspiel (exhibition catalogue)", Germanisches Nationalmuseums, Nuernberg, page 17, 1985. 19) WHITEHAUSE, F. R. B. : "Table Games of Georgian and Victorian Days", London, Peter Garnett, 1951. 20) ZOLLINGER, M. : "Zwei Unbekannte Regeln des Gansespiels", Board Game Studies 6, Leiden University, 2003. 21)Catalogo Mostra: “Le jeu de l’oie au musée du jouet”, Ville de Poissy 2000. 22) SEVILLE, Adrian: "The Cultural Legacy of the Royal Game of the Goose". Amsterdam University Press, 2019. 23) AMADES, Joan: "El Juego de la Oca", Bibliofilia Vol.III, Editorial Castalia, Valencia, 1950. |

|

| La familia Guasp | ||

Vai alla ricerca giochi Vai all'elenco autori